Little Owl is a beautiful small owl species, endangered in Europe due to habitat loss and intensive agriculture. It is a nocturnal bird of open farmland, where it breeds mostly in human settlements or large trees with cavities, such as old willows.

Acoustic monitoring – recording animals with passive recorders without human presence – has become a powerful tool for studying owls. Compared to diurnal songbirds, much less is known about owls’ vocal communication. Overnight recordings now open a completely new window into the social life of these amazing nocturnal raptors.

We recorded Little Owls in Hortobágy National Park, Hungary, and analyzed material from 2013 and 2014. It may not be surprising that our results were published ten years later. As part of my PhD, the project came with many struggles. At first, there was no existing method to process such a huge number of recordings, so I ended up with manual annotations. Once I learned how to annotate, the question was what to annotate. We originally wanted to compare male vocal activity in low- and high-density populations – a straightforward task. But there was something special about these recordings that sparked a new idea and started a long, almost never-ending journey into Little Owls’ social lives.

I was fascinated by the vocalizations of focal males. On spectrograms, I could see and hear beautiful social calls and duets between male and female, as well as the voices of neighboring males. Even though it was not our initial plan, I realized how little was known about female roles in vocal communication – especially in territorial behavior. I became the “owl feminist” of our group, insisting so long that even Martin and Pavel grew curious about female vocalizations.

Another novelty was focusing not only on single calls but also on calling sequences. In our recordings, most calls were arranged in sequences. Why? Could it be that the whole sequence carries the message, rather than the individual notes? And why were some sequences made only of hoots or chewings, while others combined both? I felt that if we analyzed only single calls, we would miss what was really happening. Once again, I pushed the idea forward, and eventually, combined hooting-chewing sequences became their own category.

Of course, colleagues and reviewers were skeptical: You didn’t record ringed individuals. You didn’t see them calling. How can you prove you recorded the same bird? It was hard to persuade them, but thanks to many earlier discussions, I knew from the beginning this point had to be crystal clear. Luckily, Little Owls are perfect for such work: their nests allow very close recorder placement, their syllables differ between neighbors, and they use relatively few calling spots around the nest. This made it possible to follow individuals throughout the night – a crucial aspect of the study.

Yes, many things could have been done better, and the recordings still hold far more potential than what we showed. But our ideas were ambitious, and I am proud that we managed to complete the project in this form. I hope this paper will inspire others to pursue their own “crazy” ideas with passive acoustic recorders – because they truly provide a unique view into animal communication.

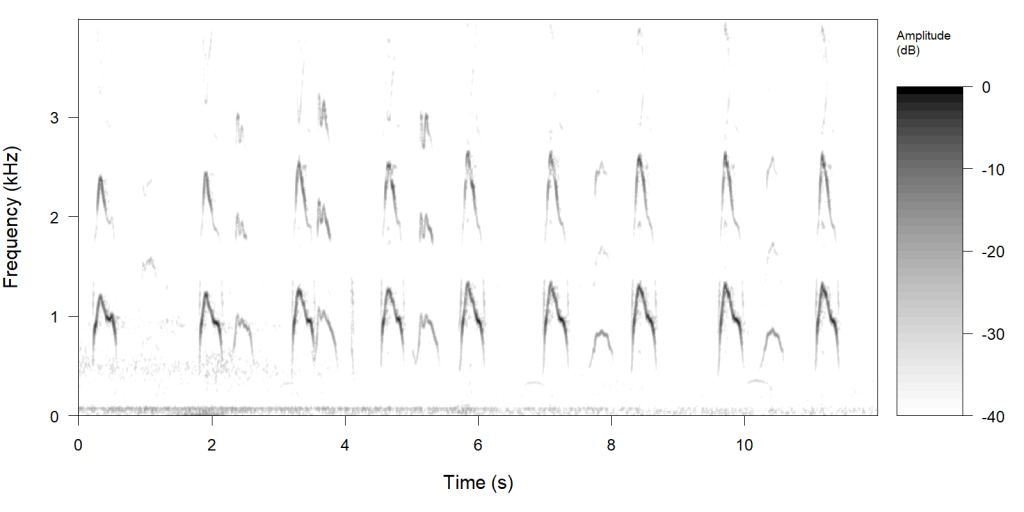

Below you can enjoy examples of Little Owl hooting, chewing, and mixed sequences.

Spectrogram and audio of a hooting sequence from a male Little Owl

Chewing sequence with background female calls and a faint long-eared owl hoot, much weaker than the Little Owl’s strong chewing calls

In this example of a mixed sequence, the male starts with hoots and gradually switches to chewing. A female voice can be heard in the background, along with a long-eared owl.